Growth Case Study: GOJEK

Gojek is an on-demand multi-service platform in South East Asia (SEA), founded in 2010 by Nadiem Makarim. Known to empower Indonesia’s digital economy, Gojek became the first ‘decacorn’ in the country — valued at more than $10b — and has expanded internationally to Thailand, Vietnam, and Singapore (Salna, 2020). Through working in their fintech group, GoPay, the author has witnessed the marvellous zero-to-one journey of acquiring millions of users and small businesses in a year.

The name Gojek derives from “Ojek”, which means a motorcycle taxi. In Indonesia, the majority of people owns a motorcycle rather than a car. It is cheaper and easier to beat traffic. However, there are problems associated with this transportation: no pricing standard, no safety assurance, and is hard to find. After finishing his MBA, Makarim saw this opportunity and started a call centre to connect customers to these drivers. Their first app was launched in 2015, followed with other services which made them the ‘tyranny-of-apps’ with $6.3b GTV/year (Gojek, 2020). Their giant head-to-head competitor is Grab, the SoftBank-backed super-app decacorn.

Growth Strategy

Achieving Product-Market Fit through experimentation

Like Google, Gojek adopts the ecosystem business model to gain a competitive advantage to reach more customers. Makarim reasoned that ride-sharing would not generate sufficient network and scale (Maulida, 2019). Strong technology development, data-driven culture and experimentation allow Gojek to generate exponential growth. Makarim (2019) mentioned how Gojek implements lean startup methodology to test product-market fit — aiming to test a product as early as possible with minimal resources. The early product-market fit was achieved when Makarim realised that customers still use the service despite the increased price and limited technology.

Gojek’s super-app started from an MVP called Go-Shop, an on-demand delivery service — a product made open-ended to deliver anything from anywhere, which generated fascinating data. Through the MVP, they noticed that 80% of the users are using the service for food. Thus, Go-Food was born, which currently has more than 75% market share in Indonesia (KR Asia, 2019). By 2019, Gojek had 22 services offered in one app (Gojek, 2019).

Super app: Building an Ecosystem & User Stickiness

Just like Amazon win the market by creating a whole ecosystem, Gojek adopts a similar strategy to dominate the market by becoming a super app for consumers. Their food delivery platform, GoFood, become has over than 75% market share in Indonesia (KR Asia, 2019). Gojek’s strategy is different from the competitors as they gain dominance from providing an ecosystem which caters to many needs of Indonesians, rather than playing in the price war game.

Gojek has also noticed that when they increase the price, people are still using the services. Thus, they know that they have achieved product-market fit. Their product testing strategy offers incentives which Nadiem thought does not need always to be cash, but could also be virality, or social capital. Thus, they Gojek is known as the brand who has out-of-the-box marketing strategies. The team concentrates on how to be the top of mind and build virality with their marketing strategy. Robust product-market fit allows Gojek to achieve high Nett Promoter Score (NPS) and virality.

Purpose-driven and Localisation

Gojek’s purpose-driven strategy is proven successful as it has become the patriotic symbol of Indonesia’s economic growth by providing millions of jobs, equals to 1% GDP (Florene, 2019). As 66% of Indonesians do not even have bank accounts (Google, 2018), Gojek offers differentiation strategies that are particularly relevant and empathetic, such as cash payment, driver top-up to serve the unbanked population, and partnership with banks to enable drivers to have bank accounts. Later, the opportunity is seized through Gopay, the financial services group.

Acquisitions & Partnerships

The rapid growth of Gojek triggers the need for partnerships and acquisitions. In customer and merchant acquisitions, Gojek utilises regional structure who understand more about the local operations. Gojek has acquired 13 companies, including MOKA, Kartuku, SPOTS, and Midtrans (CrunchBase, 2020). Gojek also partners with Google PlayStore for GoGames and Gopay, Google Maps for location services, and Google Cloud for their app development. Gojek also teamed up with the largest taxi company in Indonesia, Bluebird, after the protests against Gojek’s disruption to the transportation industry (Wijaya, 2016).

Analysis and Recommendations

It can be argued that Gojek has the first-mover advantages in the ride-hailing industry in Indonesia: disrupting the current transportation market, opening an attractive space for later players to enter (Suarez & Lanzolla, 2005). However, Gojek wins the market by achieving product-market and problem-solution fit, through reshaping their value proposition constantly (Malnight et al., 2019). Gojek is obsessed with solving customers problem; aware that people pay for solutions to the problem, not a product (Makarim, 2019; Blank et al., 2012). As an ecosystem, Gojek provides solutions to many problems. Looking at the technology adoption lifecycle theory, Gojek has proven itself to cross the chasm by changing the behaviour of consumers. Data shows that the majority of people who use the service later apparently never used motorcycle as public transportation before (Makarim, 2019).

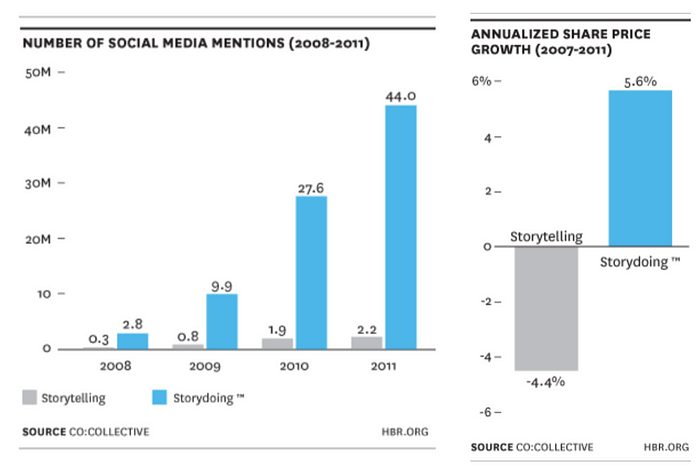

Secondly, Gojek has a distinct differentiation strategy through localisation and storytelling. Their solution through utilising motorcycle as a taxi fits the clogged-traffic problem. Uber, who has years of Silicon Valley experience, cannot keep up with the SEA competition and finally bought by Grab (Jakarta Post, 2018). Another differentiation strategy is the social impact: serving the unbanked population and creating new jobs. Malnight et al. (2019) mentioned about the importance of purpose to remain relevant in such fast-changing world. The human-centred approach in Gojek’s decision-making process creates a sustainable, long-term competitive advantage (Battarbee et al., 2015). Montague (2013) defined this strategy as ‘storydoing’, how marketing would create a significant financial impact if the company is really ‘doing’ the work. Gojek has also created a community network effect and increase awareness through virality loop (Teixeira, 2012).

Another part of Gojek’s success story is also attracting the right partners and hiring great mindsets as they invested in people since the early days. Sequoia Capital, the first VC to invest in Gojek, has been a great mentor and growth partner, according to the CEO. Later, companies like Google also becomes a growth partner which allows Gojek to penetrate more market. Gopay became one of the payment systems in Google Play in 2019 — crushing the competitor, OVO by Grab, which has been trying to win the online market by penetrating e-commerce.

However, as the company grows, the problem of people and organisation is also a core dilemma. Internally, informal communications and decision-making processes are overlapping with more than 4000 employees in Indonesia by 2019. The internal strategic theme of FOCUS, INNOVATION, and COMMUNICATION has been a core part, however, communicating to thousands of employees could be very challenging and causing cross-functional conflicts. The role of boundary spanners across regionals, verticals, and horizontals may need to be introduced to solve the challenge (Zoltners, 2019). Zook & Allen (2016) emphasises on the reignition of ‘founder’s mentality’ for leaders inside the company in order to reduce bureaucracy and increase speed.

Externally, Gojek wins the heart of drivers and treats them as an integral part of the organisation, unlike Uber who has a preference to see the drivers as independent contractors (Jakarta Post, 2018). However, this does not mean the company has a very smooth relationship with the drivers. The company has been through countless demonstrations and protests from the drivers. Some drivers even use a fake app to manipulate Gojek’s algorithm so they can gain more incentives. With Gopay, financial fraud is even worse with cashback manipulation and money laundering (Parekh, 2020). The fraud and risk faced by the company, working with lower-income partners, is a considerable challenge which needs to be tackled and outsmarted.

Winning market share in the ferocious competitive landscape is the most critical question. Gojek shares the buyer base with the direct competitor, Grab, meaning that they have the same demographics and psychographics. The ‘power users’ of Gojek services, does not necessarily mean they are loyal, as they are also more educated to the promotion. Nevertheless, Gojek needs to monitor the saturation of growth continuously and increase market share through penetrating new markets, followed by the average purchase frequency. Gojek also needs to defer using subsidies to test product-market fit as it may cause confusion and negation of the real data.

In terms of balancing between financial incentives and non-financial incentives in growing the business, Gojek needs to continue doing ‘smart business’ like Alibaba (Zeng, 2018), which means utilise their ecosystem of data to automate decision-making. Promotions should be treated as a long-term strategy through experimentations. As Gojek runs more than dozens of experiment per day on average, prioritisation becomes key to reduce bias in a very crowded environment. Building the ‘insights engine’ for competitive advantage requires a balance between creativity and analytical thinking (Driest et al., 2018). The incentives given to users are part of a more significant experiment to validate the hypothesis and determine the right strategy in the future. With a steady pace and investment to scale, Gojek has to focus on the long-term approach and not just running up the numbers (Sutton, 2014). Gojek needs to continuously identify new ways to instil top-of-mind in the market rather than only going wider and offering new value propositions. Mohammed (2012) argues that the way to boost sales from customers is more than saying ‘our product is better’, but it generates more ‘profit’ — instil more value. Customers are currently stretched with options in the market, which increase the needs of balance between minimising price and value for money. Some ways to handle the pricing strategy would be framing higher price as ‘upgrade’, translating to tangible benefits, and stack up discounts in order (Hardisty et al., 2020).

Gojek has been doing has created a network effect and increase awareness through virality which they have created. People get bored easily nowadays as there are too many sources of information, and they have increased control over what they want to see. Thus, continuing a viral loop of emotional ‘roller-coaster’ is essential — surprise, not shock (Teixeira, 2019). However, as Gojek’s marketing strategy need to be deep enough to attribute values from the ads to become more effective.

Profitability has always been a big question to reach the IPO goal. Moreover, Uber’s IPO losses have raised concerns about other ride-hailing unicorns (Siddiqui, 2019). The company may generate billions of dollars in revenue, but Gojek is not remuneratively lucrative yet. Ride-hailing service in Gojek only represents less than a quarter of GMV (Suzuki, 2019). The only segment generating the highest cut for Gojek is only the food delivery commission, which takes a 20% cut of each transaction. Govindarajan et al. (2018) also mentioned the importance of emphasising business model success factor, rather than merely financial statements, to capture the intangible investment for the digital ecosystem, such as network effects.

Before COVID-19, WSJ predicted Indonesia to be the fifth in the world in terms of #users for the ride-sharing market (WSJ, 2017). Nevertheless, COVID-19 crisis has been a hit to the online transportation industry as people travel significantly less, and BCG consumer report showed how people would be more likely to remain working from home even after COVID (Jacobides & Reeves, 2020). Gojek was also forced to diminish GoLife services due to slow growth, followed by laying off 430 employees — 9% of total headcount (TIA, 2020). However, Gojek’s diversification strategy has helped the survival of drivers to perpetuate for Go-Food, Go-Send to deliver parcels, and Go-Mart to buy items from the supermarket. Thus, the pandemic has not ceased the company’s growth and instead convert more merchants to move from offline to online businesses. GoFood’s number of merchants has been incrementing by 24%, and 43% of merchants who joined between March-August are first-timer who tries to make a living amidst the crisis (University of Indonesia Research, 2020).

Moreover, the advent of Go-Games and Go-Studio in late 2019 was a brilliant and timely strategy for in-home entertainment. However, the ride-hailing business may need to reconfigure the services ahead to reduce concerns cognate to safety and gain trust from consumers. In times of uncertainty, Jacobides & MacDuffie (2013) argues that companies like Google and Apple are hard to be superseded in the value chain as they have become a “system integrator.” If Gojek wants to thrive in the industry, they need to be present and flexible to move their value proposition along the value chain.

In the long run, to reach international expansion, Gojek needs to be vigilant of localisation. Gojek’s business model and disruption may work in Indonesia, but making the model work in another country is a whole different story. Moreover, Grab and Uber, their main competitor, has been a player for a while in SEA. The main problem is the limited knowledge of the market, and a limited range of services causes the loss of appeal (Bastian, 2020). Thus, Gojek needs to find the ‘impact gaps’ continuously, build strategies to touch individuals and sticks (Sutton, 2014). There are five strategies, according to Wessel & Christensen (2012), to increment advantage barriers: momentum, tech-implementation, ecosystem, new technologies, and business models. Also, the core of defensibility strategy from other disruptor and competitor stems from how well Gojek can serve customers’ jobs and adjusting BM (Wessel & Christensen, 2012). Growth is a full system with linkages to the whole business, and the ‘Why’ of the company has been the core of Gojek’s hyper-growth for a decade.

Disclaimer: This case study was done as a part of a master’s degree study in 2020 by the author. It is also done not as a critic against the company, but to analyse growth opportunity and strategy that can be offered.